Dear People, Neighbours, and Friends of St. Thomas’s,

On Wednesday, the Diocese of Toronto sent an email to clergy and wardens that stated in part, “Although the Province of Ontario will be lifting mask mandates in most settings on March 21, churches in the Diocese are still asked to follow the Spring Guidelines for the time being. We will be re-evaluating our guidelines in light of the government’s decision and will communicate to you about them as soon as we’re able.” As of this writing, we have not received any further details.

The reference to the “Spring Guidelines” is to a document that, among other things, states that “Masks continue to be mandatory in our buildings.” Until further guidance is received from the Diocese, the consensus is to comply with the Diocese’s request in maintaining our mask mandate. This is unquestionably the case for Sunday, March 20, since the provincial mandate is still in effect until the next day. We are hoping that by next weekend, we will have greater clarity from the Diocese.

The most recent update from the Diocese confirms that social distancing is no longer mandatory and that households not related to each other may share pews if mutually agreeable. Before sitting in a pew occupied by others or directly in front of or behind an occupied pew, please check in with your nearest neighbour(s). For instance, asking, “Do you mind if I sit here, or would you prefer to maintain distance?” is a neutral way of posing the question that gives the person being asked the freedom to reply honestly and with a minimum of awkwardness. Some people will prefer to maintain distance, and this ought to be respected. The sidespeople can be of help in finding a place where you are most comfortable sitting, but ultimately we will all have to develop a new etiquette for ensuring that we are being as considerate of each other as is humanly possible.

I commend to you the pastoral words of Fr. Shire below.

Yours in Christ’s service,

N.J.A. Humphrey+

VIII Rector

Mask Mandates

Dear Friends in Christ,

The COVID-19 pandemic has been a challenge for all of us. We have all experienced the difficulties, frustrations, and exhaustion of the lockdowns, social distancing, online school or work, travel restrictions, and, of course, masking. All of these have been used as tools in the effort to slow and halt the spread of the virus in society, and though we may have experienced varying levels of isolation due to these measures, we could take solace in the fact that in our commitment to each other, we were all in this together. We were doing all these things out of care for our neighbour, and such care is rooted in the Gospel message “Thou shalt love thy neighbour as thyself.” To be sure, following the Gospel in this particular way has been and continues to be, to put it mildly, both tiring and trying, but our collective efforts did buy the world time to produce effective vaccines and pharmaceutical treatments for COVID-19. Though the future trajectory of the scourge of COVID-19 is unknown, we can say that we are in fact in a far better position now than we were two years ago. With God’s help, we did our best to demonstrate a spirit of cooperation, compassion, and care for one another, even if it was from two metres away or over a Zoom meeting.

And now we are entering into a new phase. With high vaccination rates and increasing access to COVID-19 treatments, public health measures have slowly been repealed in Ontario and across Canada. Capacity limits have been lifted, the vaccine passport system has been suspended, and beginning on March 21 the indoor mask mandate will be lifted for most places, except for those high-risk locations which will remain under a mandate until April 27 (which includes our own Friday Food Ministry).

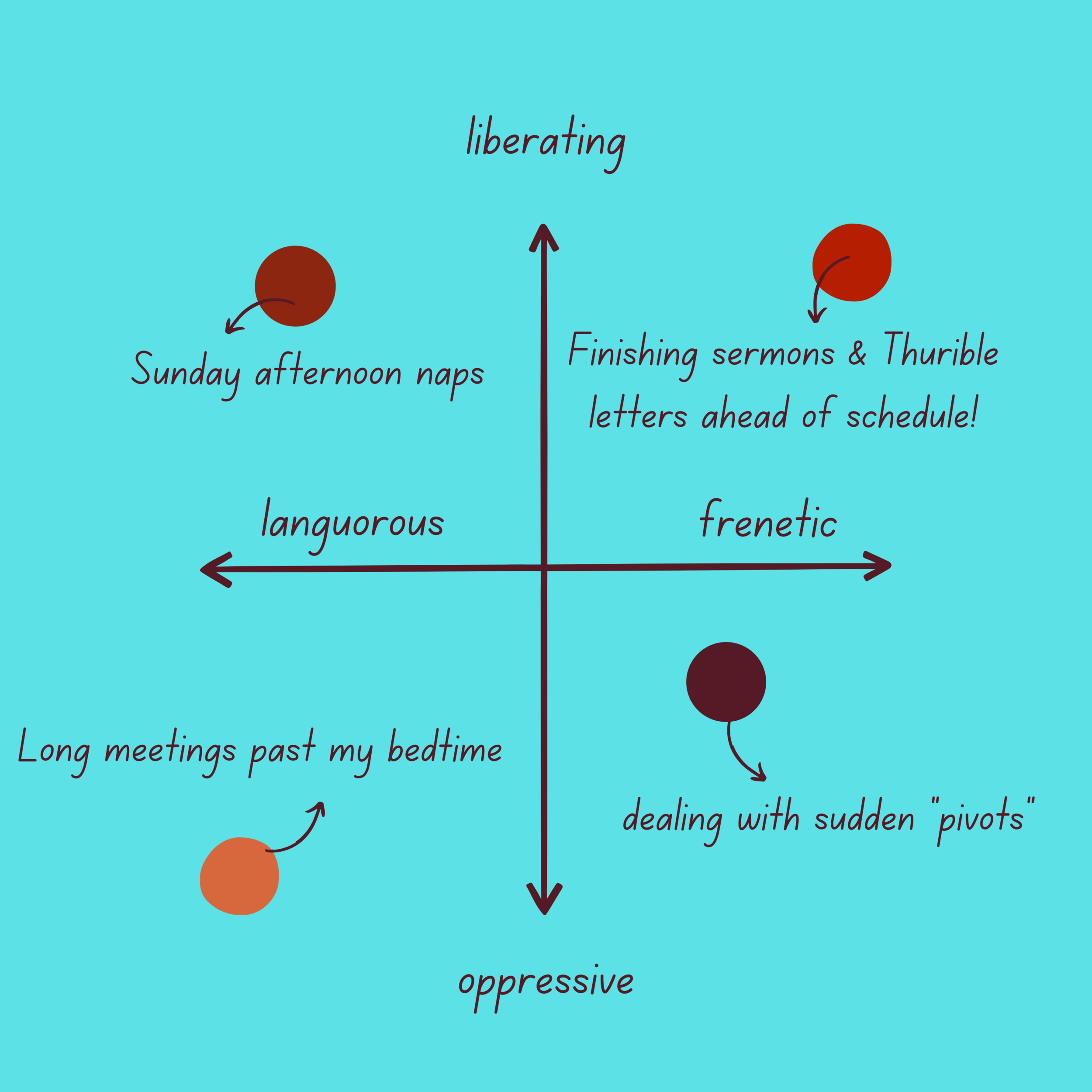

Understandably, collectively we are approaching this March 21 date with mixed feelings. Some of us may be rejoicing that masks will be gone in most places; it is a sign to some that the pandemic really is over, and we can go back to our lives without constraint. Others among us are concerned that such a move may be premature, and there’s a sense that case numbers and hospitalizations need to be even lower than they currently are before lifting these measures. Some of us may work or live with people who are at higher risk for severe symptoms and outcomes from COVID-19. We may have loved ones who cannot be vaccinated due to their age. For many of us, masking continues to be a necessary precaution taken out of concern for the safety of others. And of course, a significant number of us in the St. Thomas’s community are ourselves immuno-compromised or at higher risk for severe symptoms and outcomes from COVID-19, and so we continue to use masking as a tool to keep ourselves as safe as possible under any given circumstances.

The truth of the matter is that we are all in different places and may have different attitudes about this new phase of the pandemic, and that is okay. But how do we navigate these uncertain waters? How do we balance our own feelings, needs, and wants with the feelings, needs, and wants of others?

From my perspective, though we may have experienced this pandemic in varying degrees of isolation, we did try to live at all times in a spirit of cooperation, compassion, and care. If we enter into this new phase with that same spirit of cooperation, compassion, and care that we have endeavoured, with God’s help, to show each other since March 2020, we will be better able to be gentle with each other and ourselves.

We are all in different places mentally, emotionally, and spiritually when it comes to the lifting of the mask mandate. We may feel anger and frustration if we see others unmasked while we are masked indoors. Alternatively, we may find ourselves angry and frustrated if we see others masked while we are unmasked indoors. Some of us will feel guilty for enjoying the loosening of restrictions; it may feel strangely transgressive. We will encounter these and a variety of other feelings in our own church building during our liturgies, and such feelings may be heightened when we see others acting differently from where we have landed.

As a community, though, we must, as Titus 3:2 puts it, “avoid quarrelling, be gentle, and show every courtesy to everyone.” We all have different levels of comfort and different ways of assessing risk, and we must respect and affirm this reality with humility and with that same spirit of cooperation, compassion, and care. Whether in person or away from each other, we are still one community and family, and, as such, mutual respect is key in how we think of and relate to each other as we enter into this new phase of the pandemic, even if we find ourselves in a different place from others in terms of our assessment of what constitutes acceptable risk. Wherever we land on that question, we are still all in this together, and whatever the future may hold, I am certain we will be able to face it as one community if we rely on the grace of God to give us the power to show God’s grace and love to one another.

Fr. James Shire