Dear People, Neighbours, and Friends of St. Thomas’s,

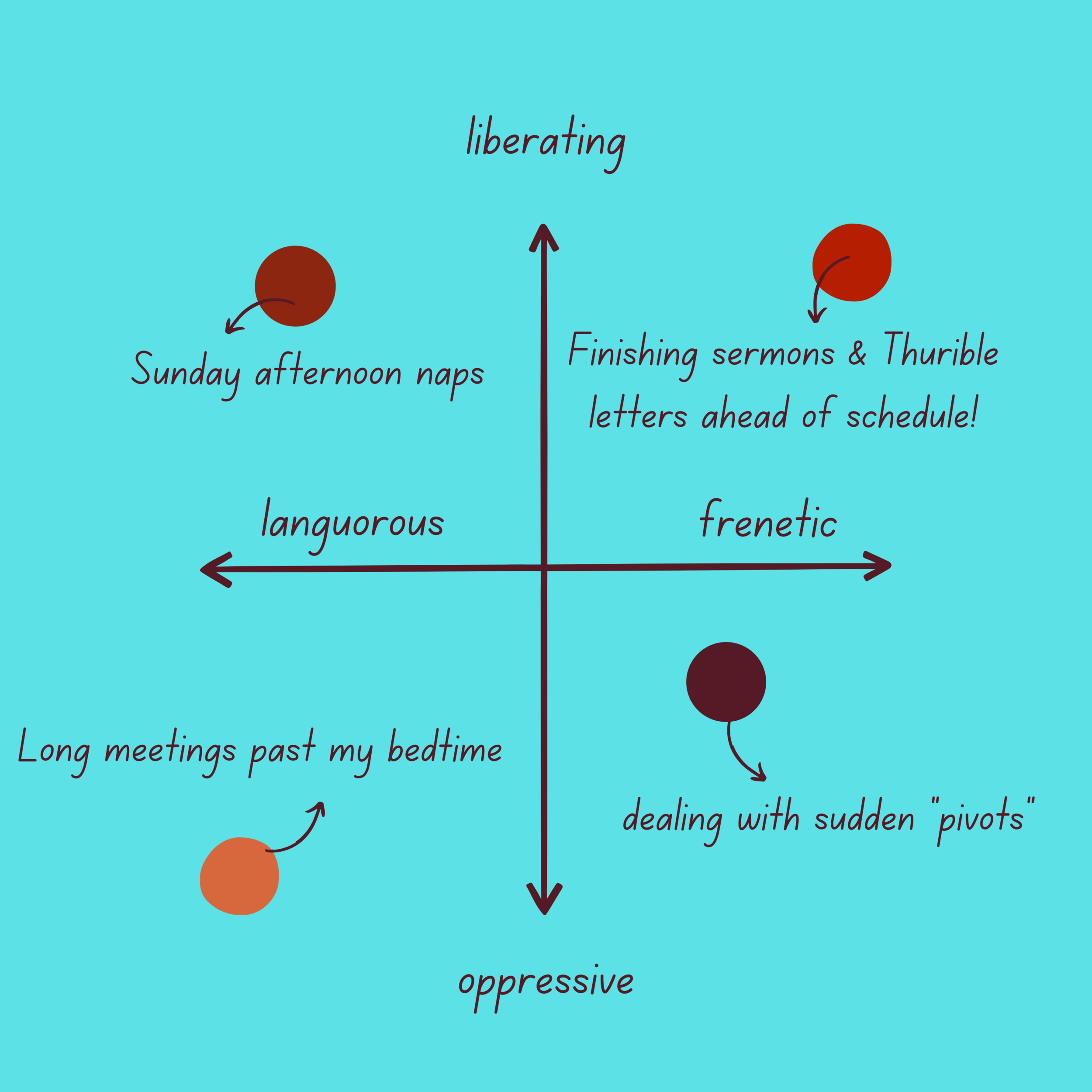

This Sunday, January 16, 2022 will mark exactly six months since my family and I arrived in Canada. Because we are living through such a strange stretch of world history, I feel like I have been existing in a sort of time warp that alternates randomly between frenetic and languorous, each state characterized by some measure of either the oppressive or the liberating. If I were to try to map my state of mind and body in an average week (or even an average day), it would look something like this:

Wherever I am at the moment, I often find myself torn between seemingly opposing desires: the desire to rest and the desire to be productive; the desire to be creative and the desire for structure. This is as true of my home life as it is of my work life, because I’m the same person wherever I am and whatever I’m doing. I’m as flawed and as gifted at home as I am at work, though each sphere gives me different opportunities to display my weaknesses and my strengths.

Even were we in “normal” times, I suppose this all would still be the case, but for the past two years, it seems like every desire I have feels so much more intense (or numbing), the stakes so much higher (or irrelevant), when we are suffering and hoping, working and waiting for a better tomorrow.

This theme of desires came up in my reading recently. The context is that over the next four Thursdays, Fr. D’Angelo and I will be facilitating a noonday discussion group on Julia Gatta’s Life in Christ: Practicing Christian Spirituality. (See details here.) The author is the professor of pastoral theology at the School of Theology at Sewanee, a seminary of the Episcopal Church. While I already had the book in one of the many, many boxes of books we lugged off the moving van six months ago, it was Fr. D’Angelo who suggested it might be a good way to examine the content and practice of the Christian faith in a distinctly Anglican mode. Our conversations will be geared towards those who are considering baptism or confirmation as adults and those who want an introduction (or refresher) to Anglican spirituality and Christian discipleship. Do join us if you can.

In the introduction to Life in Christ, entitled “The Heart’s Longing,” Professor Gatta writes of “the ache of the human heart for something transcendent.” Like many spiritual writers before her, she claims that “God has instilled this infinite desire in us precisely so it might lead us back to Infinite Love.” It is “God’s desire for us that animates our desire for God.” Her stated purpose for the rest of the book is to describe the ways that Christians, particularly “in churches of a catholic character, including the Episcopal and Anglican tradition,” attempt to respond to this desire, to “drill down to the source of these desires, attempting to name and embrace it.”

Prof. Gatta goes so far as to claim that “all our true needs and desires fall under the scope of God’s care. When our desire for God is acknowledged, when we boldly pray…for the reality of God to take hold and move us into the vast abyss of divine love, these other legitimate but subordinate desires gradually fall into place.”

I might even go further and say that all our needs and desires, whether they are “true” or “artificial” (as, for instance, the desires that consumer culture attempts to inculcate in us) are under the scope of God’s care, for it is only when we submit every desire to God that we are given the grace to see them for what they really are, and equipped by God to order them or dispose of them as God might will us to do. That is to say, even our most sinful, shameful, hurtful, and wretched desires, when dragged kicking and screaming into the light of Christ, lose their power over us, and can even be redeemed, given back to us in a transformed way that enlarges and softens our hearts towards each other. God takes away the shrunken and sclerotic desires of our hearts of stone and gives us revivified hearts of flesh.

Does this sound hopelessly idealistic or unbearably romantic to you? Perhaps a classic example from Scripture will demonstrate my point. In Genesis chapter three, we are told that when Eve looked at the fruit of the Tree of the Knowledge of Good and Evil, and “saw that the tree was good for food, and that it was a delight to the eyes, and that the tree was to be desired to make one wise, she took of its fruit and ate; and she also gave some to her husband, who was with her, and he ate…” Notice those three specific things that motivated Eve: she is tempted by the fruit because it “was good for food,” “a delight to the eyes,” and “to be desired to make one wise.”

We find a sort of commentary on these three categories of temptation in the First Epistle of John: “Do not love the world or the things in the world. The love of the Father is not in those who love the world; for all that is in the world—the desires of the flesh, the desires of the eyes, and the boastful pride of life—comes not from the Father but from the world. And the world and its desires are passing away, but those who do the will of God live forever.”

The “desires of the flesh” corresponds to Eve’s seeing the fruit as “good for food.” “The desires of the eyes” corresponds to Eve’s seeing the fruit as “a delight to the eyes.” And what I translate here as “the boastful pride of life” can be correlated to the fact that the fruit was “desired to make one wise,” that is, Eve desired it because she believed it would confer power, so that she could rely on her own strength and abilities apart from God. In short, that fruit represents every desire known to humanity, and the potential that any of our desires has to be used, not as a way to deepen our desire for God and experience God’s desire for us, but to make idols of people, things, and powers we mistakenly think can give us our heart’s desire better than God! We idolize other people (or ourselves) by relying on them (or ourselves) to bring us a sense of contentment and fulfillment. We look to things—anything at all—to give us a sense of purpose and meaning. We worship power, and fame, and wealth (either our own or others’) to make us happy or at least to keep us entertained, distracted, or occupied, and we find that nothing fills the God-shaped hole in our hearts. As St. Augustine of Hippo famously wrote, “You have made us for yourself, O Lord, and our heart is restless until it rests in you.”

But there is an alternative. When we pay attention to our desires, whether they are noble or base, and if we offer them up on the altar of the true and living God, we find that God works through those desires—all of them—to turn us from the worship of idols and toward a relationship with God in Christ through the power of the Holy Spirit. This relationship leads to true life now, and in the age to come, life everlasting. This claim is neither romantic nor idealistic. The process of sacrificing our desires on the altar of the cross so that they might be redeemed to God’s glory and our sanctification takes a lifetime. We have to dedicate “our selves, our souls and bodies”—in all their splendour and wretchedness—again and again.

Some days we approach this life of Christian discipleship with oppressive languor, at other times in a rush of liberating freneticism. Most of the time, we’re somewhere in between, and occasionally we feel like we are living a quotidian existence that is directionless and disorienting. How then shall we live? We find the answer to that question in prayer. The sort of prayer I have in mind may be described as laying every desire bare at the feet of Jesus, and begging the Father to send the Holy Spirit to transform our desires so that they lead us back to their purest and highest Source, where we may abide in the Presence of the God of Love, who gives us life in Christ.

Yours in Christ’s service,

N.J.A. Humphrey+

VIII Rector