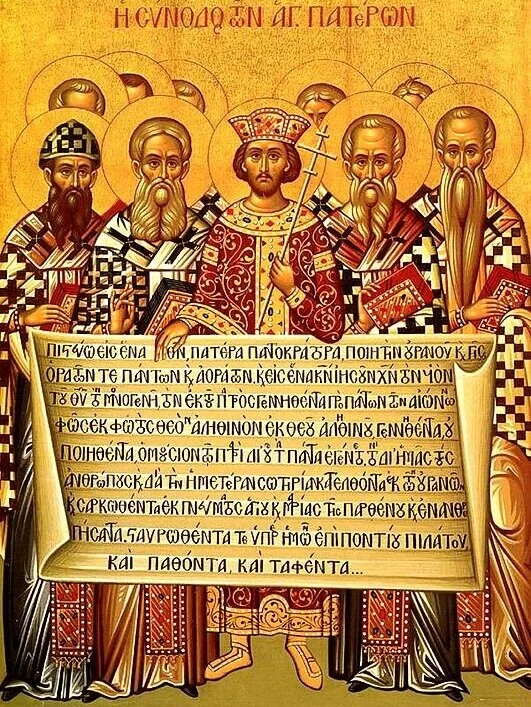

Icon depicting the Emperor Constantine, accompanied by the bishops of the First Council of Nicaea (325), holding the Niceno-Constantinopolitan Creed of 381. Unknown author, public domain, via Wikimedia Commons.

Dear People, Neighbours, and Friends of St. Thomas’s,

One of the wonderful things about St. Thomas’s is that both the clergy and laity truly care about what happens in the liturgy. We get the connection between praying and believing. How we pray shapes how we believe, and what we believe shapes how we pray, and how we live. This principle, known as lex orandi lex credendi, is central to who we are not only as a parish but as Catholic Christians.

The basic statement of our faith is found in the Nicene Creed, which originated as a refutation of the Arian heresy. While I’d love to get into all of the details of the formation of the creed in this letter, Wikipedia does a far better job in this instance than I could do, and as you will find, this letter is long enough without it! The interesting thing to me is that this lex credendi only gradually made its way into the lex orandi of the Church, and despite schisms and heresies, including over the content of the creed itself (and especially over the filioque), the Niceno-Constantinopolitan Creed, as scholars refer to it, in fact stands as the defining statement against which the orthodoxy of all churches can be judged. In short, Nicene Christianity is Mainstream Christianity, such that if any of the churches that regard ourselves as “mainstream” were to drift from the creed, we would no longer be recognizably mainstream. The Nicene Creed is the gold standard of Christianity.

Recently, I could not resist placing the Nicene Creed after the sermon at the eleven o’clock service. It was already in this position at the 9:30 service, and I found it disorienting to flip from one order of service to another. I was afraid I’d go on autopilot and launch into the sermon after the Gospel, when I was supposed to be back at the altar leading the creed first. But the rubric in the Book of Common Prayer is to have the creed precede the sermon. What right have I to break this rubric? I have a great respect for the rules, after all. But at St. Thomas’s, we already break several BCP rubrics, such as placing the Gloria after the Kyrie, the Lord’s Prayer before the Fraction. What’s one more little rubric?

Well, it turns out it’s pretty important in the history of liturgy, though it also turns out I stand on pretty solid ground in disregarding it. The use of the creed in liturgy in the Anglican Communion has been informed by two broad streams: the Roman Rite, and Anglican reforms of that rite based on various sources, including other ancient usages such as Sarum, as well as reforms of the liturgy introduced by English and continental reformers. Liturgical reform and renewal have carried on as a process right on down to our own day, through many a schism. If such liturgical debates are of no interest to you, feel free to skip the rest of my letter, which is essentially a report of various conversations I’ve been privileged to listen in on concerning this topic.

I decided, at the urging of a parishioner, not to make such a change based on my own whims but only after thoughtful reflection and study. Accordingly, I posed the question of whether the sermon belongs before or after the creed to several people, including members of a Facebook group I co-founded called, of all things, the Nicene Coalition.

One Coalitionist, a doctoral student named Drew Nathaniel Keane, started with a survey of the Reformed tradition within Anglicanism. (Some of you may recall his presentation via Zoom this past Lent as a part of our multi-parish series on the Eucharist in Time of Pandemic.) As it so happens, he wrote a chapter of his doctoral dissertation on this very question! Mr. Keane replied:

In The Acoustic World of Early Modern England (1999), Bruce Smith maintains that the Prayer Book’s ordering of creed followed by sermon “represents a particularly significant departure from the Roman liturgy” that reflects a uniquely reformed perspective, “Acknowledgement of belief becomes a condition for hearing God’s word preached, not an effect” (p. 266). Whatever one may think of Smith’s reading of the implicit theological statement of the relative positions of the creed and the sermon in the Prayer Book, he is mistaken in claiming Cranmer reversed the relative positions of creed and sermon in the pre-Reformation Roman liturgy. Neither the sermon nor the creed were invariable elements of the pre-Reformed Mass. Procter and Frere (1907) indicate that in the Use of Sarum (the most widely used local adaptation of the Roman Use in England), when the creed was said (on Sundays) and there was a sermon (which was not required for Sunday mass), the sermon followed the creed (p. 469) just as in Cranmer’s ordering. In contrast to the prevailing modern Roman Catholic practice, Durand, 13th-century Bishop of Mende, places the sermon after the creed in his exposition of the liturgy, which order, Jungmann (1986/1951) notes, still prevailed in some dioceses, such as Trier, in the mid-20th century (p. 456). According to Jungmann, in some places the sermon was preached after the reception of the offering, while in England and France in the late middle ages, the sermon was “usually inserted after the Orate fratres” (ibid). Campbell (2018) indicates the relative position of creed and sermon varied in different places (p. 123), as does Maskell’s (1846) study of the medieval Uses of Sarum, Bangor, York & Hereford.

In other words, solid evidence exists for either ordering (creed before sermon or sermon before creed), and the question of whether one order should be given priority over the other has been a subject of debate, conjecture, and ultimately, liturgical variety. Mr. Keane continues:

In 1610 John Boys, commenting on the relative order of creed and sermon in the Prayer Book liturgy observed: “the Nicene Confession after the Gospell and Epistle: because faith (as Paul teacheth) is by hearing, and hearing by the word of God. We must first heare, then confesse for which cause the Church of Scotland also doth vsually repeate the Creed after the Sermon.” This runs contrary to Bruce Smith’s theological rationale for the relative placement of the Creed and the sermon. Smith inferred from the order that only those with faith (indicated by saying the Creed) could profitably hear the sermon. Boys says the Creed follows the scripture readings because hearing the word produces faith. Indeed, while Boys observes that in Scotland [the practice] is for the Creed to follow the sermon, he draws no theological significance out of the (different) order in the Prayer Book.

The Very Reverend Andrew McGowan, Dean of my alma mater, the Berkeley Divinity School at Yale University, observed that, “It’s not the Creed that’s moving, it’s the sermon. There wasn’t a sermon there in the Sarum missal, it was added in 1549 and then the adjustments etc. follow based on various theological arguments (and maybe Patristic models).” Mr Keane concurred, adding, “Indeed, the position of the Creed (though not necessary for every Mass) became fixed long before the position of the sermon (which was also not necessary for every Mass). The real innovation of the Prayer Book in 1549 is not the relative order of these elements but that the rubrics require both of these elements for every celebration of the Lord’s Supper.”

In our own congregation, Dr. Barry Graham, whose doctorate is in medieval liturgy, also took note of two of the main historic resources Mr. Keane drew upon in his chapter, and helpfully provided this background for me:

The two most valuable historical sources I’ve found to date have been Josef Jungmann, a Jesuit of the early 20th century, and William Durand, bishop of Mende in southern France in about 1293. Jungmann’s The Mass of the Roman Rite traces the Mass’s evolution over two millennia. Durand’s Rationale Divinorum Officiorum gives a detailed analysis of the contents of the mass as it existed in 13th century Languedoc. Its ideas were highly respected at the time and were adopted at Trent and survived until Vatican II in 1963.

Jungmann tells us that in the first millennium, sermons were restricted to bishops until 529 because of insufficient formation (a.k.a. ignorance) of the lesser clergy. So until 813, sermons by the lesser clergy were translations of the homilies of the church fathers, which were read. The creed followed the last lesson or homily (if there was one) on Sundays and certain feast days. So if the creed was said when there was no homily, it cannot have been intended as an acclamation of the homilies’ contents.

Dr. Graham’s concern was rightly that the sermon should not outweigh the creed in importance, nor be seen to imply that an imprimatur and nihil obstat are to be accorded the preacher’s words. In this understanding, he wrote, “The creed should follow the gospel, not the homily. The creed affirms belief in what it immediately follows. We believe the gospel, not the homily. Following the homily makes it appear as an ego trip on the part of the homilist.”

Far from exalting the homilist, the overwhelming majority of my respondents emphasized the humbling power of the creed vis-à-vis the sermon. Lay theologian Liza Anderson recounted with humour how a mentor told her that “the creed was placed after the sermon so that the congregation could refute whatever heresies had just been uttered from their pulpit.”

Indeed, Fr. John Alexander, the retired rector of the staunchly Anglo-Catholic parish of St. Stephen’s, Providence, Rhode Island, demonstrated the humility every preacher should have when he remarked, “I often think on my way back to the Altar from the pulpit, ‘Whatever mistakes I may have made, now we have the opportunity [in the creed] to put it right!’”

Nowadays, we might suspect that some preachers are not so much ignorant as they are disdainful of the contents of the creed. Sadly, I have often heard sermons that treated various doctrines enshrined in the creed as expendable. Similarly, Professor Jesse Billett of Trinity College around the corner provided this informative footnote:

He remarked to Dr. Graham that he imagined “the reforms of the 1960s and ’70s aspired to give the homily a more organic connection to the scriptural readings, such as it seems to have had before the Creed was inserted.” I resonated with his humorous admission that, “after many a homily I’ve found it useful to rise and begin the Nicene Creed by saying under my breath, “NEVERTHELESS, I believe in One God…”

Canon Jeremy Matthew Haselock, a household chaplain to Her Majesty The Queen, whose liturgical scholarship in the Church of England is well known, succinctly remarked that the liturgical ordering of sermon before creed has its own logic: “the Gospel is read/proclaimed; the Gospel is expounded in the sermon; the people proclaim their baptismal faith with greater conviction.”

Greater conviction. This is, after all, the goal of the proclamation of the Gospel both in its sacred text and faithful exposition. Wherever one puts the creed, its authority always outweighs that of any individual preacher. We are right to avoid in liturgy any impression that the sermon is the “main event” because as sacramental Christians, the sermon may help us love God and neighbour, but it is the Eucharist that is the means of grace by which we join ourselves body and soul to the Presence of Jesus, and are thus equipped with the ability to live up to the challenge of a fine sermon, and the fortitude to disregard an unedifying homily…or overlong rector’s letter.

Yours in Christ’s service,